BRIEF FROM ORGANIZATION AND

SYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT INC./SOFTCARE

Private Capital for Public Gain

Executive Summary

Canadians' demand for publicly-funded healthcare and social services is growing faster than the economy. The challenge for government is finding ways to reduce care costs while assuring quality care so that growing demand can be met from current funding. One way is broadening the use of productivity measures and methods in service delivery processes. At an average rate of productivity increase of 25%, savings can offset the need for increased funding for three or four years; at 50%, for a decade or more.

In a time of deficit spending, government needs access to new, private capital. Private investing for public gain is not new, but private charitable donations are inadequate to meet this capital demand. The alternative is Social Impact Financing, a true investment model, capable of attracting the needed capital. Social Impact Financing is evidence-based, with measurable social impact and return on investment. Investors place their money into social investments that generate measurable public benefit. The measures of that benefit are valuated and validated by third-party audit. Investors make a return that is a portion of the value of the social impact in public savings.

Seeking productivity savings is risky, but one that is regularly managed in the private sector. Turning private experience to public ends requires a public incentive that government can control. While Social Impact Financing can be administered directly by government, it can also be administered indirectly, as a tax incentive, at lower cost. Annual claims for tax credits provide a level of transparency that greatly facilitates government control of the critical ratio of public to investor returns, as well as bringing government participation after the fact of both the investments and the savings to minimize public risk.

Social Impact Financing (SIF) commercializes public return on private investment, putting private capital to work for public gain.

Recommendations

1. that Canada promote cost control, cost reduction and savings in publicly and charitably-funded, professional healthcare and social services with broader use of productivity measures and methods in service delivery processes;

2. that Canada employ Social Impact Financing as a method of attracting private capital into the development and implementation of service delivery innovations that increase service productivity generating public savings;

3. that Canada employ tax incentives to administer and control public and investor returns in Social Impact Financing, to ensure maximum public gain while providing reasonable investor return.

Introduction

The demand for publicly-funded healthcare and social services is growing faster than the economy. Canada's growing, aging and increasingly diverse population assures increasing demand. The conventional method for meeting growing demand requires direct and proportional increases in public spending. But increasing public spending, to keep up with this demand, sustains government deficits and displaces other government spending priorities. Canada needs more publicly-funded healthcare and social services, for less cost. To reduce care costs and increase care cost control, the challenge is finding the right care measures, valuating changes in those measures, and validating the valuation of those changes.

Last year, the Auditor-General of Canada earned a standing ovation with a speech to a national gathering of professional caregivers. In her speech, she reported that for all the many measures of healthcare currently reported, there is no way to judge the value of billions of dollars of public spending, and no way to forecast where spending should go. The issue is not the lack of spending control. Spending cuts are made resulting in direct and proportional cuts in services to Canadians. The issue is how to migrate from budget control to cost control in order to glean more service from existing care dollars.

Measuring and Valuating Care

Health and social services funding buys care - the care that qualified practitioners provide to eligible clients. Care is rendered in a succession of planned, service transactions, each with a duration of hours and minutes. Changes in the use of practitioner time give meaning to other service performance measures. For example, an agency proudly reports a 20% increase in the number of clients served. But, the agency also reports that the number of hours of service per client remained the same, so that more clients got less care. Similarly, a report of a 37% decrease in wait time does not indicate in itself an increase in performance. If, however, the hours of care per client increased from period to period, and wait times decreased between those same periods, then performance did indeed increase. Care is the time practitioners spend working with their clients and this measure gives meaning to other service performance measures.

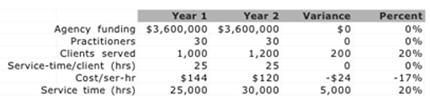

Care time can be valuated. For example, the report, above, shows that the agency used $3.6 million in funding to employ 30 practitioners to serve clients. These 30 practitioners were able to serve 1,200 clients this past year vs. 1,000 the year before, at the same level of care.

In the table, above, funding remained the same from year 1 to year 2, as did the number of practitioners. The number of clients increased by 200, or 20%, while the average time spent by practitioners with their respective clients remained the same, at 25 hours per client per year. However, because of the increase in the number of clients served, the total care time rendered by the practitioners with clients for the year increased by 5,000 hours, representing a 20% increase in their productivity. This increase in care productivity represents a saving of $720,000 (5,000 hours of care @ $144 per hour) that year, to the agency and its funder. Introducing care productivity provides the needed measure and valuation for reducing care costs and increasing care cost control.

More Care, For Less Cost

Professional practitioners provide healthcare and social services to their clients. Their work of highest value is the care that has taken them years of study and practice to qualify to provide. Their work of highest value has been steadily shrinking over the years, as a result of increasing demands on their time for such things as case recording, service reporting, retrieving and reviewing information, and coordinating their work with a growing numbers of colleagues. Savings on services are achieved with the use of technology that facilitates re-tasking practitioner time, from activities supporting client services, to working directly with clients .

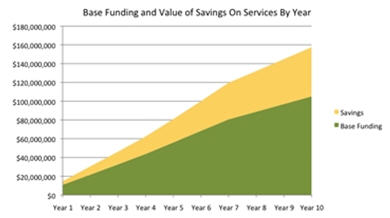

Enabling practitioners to change the allocation of their work time among different service delivery processes can increase their productivity. In eleven agencies providing a variety of publicly-funded healthcare and social services, private investments of $9 million enabled 177 practitioners to increase their productivity by an average of 54%, delivering $50 million in new client services, as illustrated in the chart, below.

The yellow area illustrates the relative size of the value of the new services (the savings) realized with productivity gains. The green area illustrates the relative size of base funding provided by government each year to these agencies. These private investments demonstrate the potential of productivity to deliver more care to Canadians, for less cost.

Challenges To Change

While productivity measures and methods provide a means to reducing care costs and increasing care cost control, the question is how government can scale changes in the patterns of service delivery from savings of $50 million, to $50 billion? Some of the principal challenges are:

1. $50 billion in savings will cost $10 billion to achieve and in a period of fiscal constraint government will need new sources of capital;

2. with many provider agencies running operating deficits, finding capital for the first three years of productivity changes equivalent to 15% of their operating budget will not be possible;

3. productivity is not currently taken into account in the funding or delivery of publicly-funded healthcare and social services, and public administration lacks the experience of managing the risks of productivity investments;

4. building awareness of productivity measures and changes across the thousands of public and private organizations providing hundreds of publicly-funded healthcare and social services programs in Canada will take time:

· many professional practitioners do not view productivity as having any bearing on how they deliver services;

· some executives declare that their people simply cannot be asked to work any harder;

· some public funding agencies make extraordinary demands on practitioners to report pages of data on every client every few months, consuming, in the process, 25% of available practitioner time to care for clients;

· some public administrators "have no use" for productivity measures or the value of savings productivity increases have generated;

· an observation recently offered by the dean of a national school of management at a conference on productivity, about the absence of any reference to productivity in public healthcare, was “because nobody cares”.

Seeking productivity savings in publicly-funded healthcare and social services is a challenge, not only in identifying social innovations that will yield real, measurable results, but also in deploying those innovations among the thousands of public and private organizations providing these services to Canadians.

A Strategic Choice

Social Impact Financing is a form of social financing involving private capital, like charitable donations, but with greater potential for marshalling the hundreds of millions of dollars needed to launch productivity investments. Unlike charitable donations, where the investor is expected to be out-of-pocket, Social Impact Financing is a true investment model. Social Impact Financing is evidence-based, with measurable social impact and return on investment. Investors place their money into social innovations that are offered free-of-charge to publicly-funded healthcare and social service agencies. These innovations enable agencies to maintain quality care, increase their accountability to funders, and meet growing demand for their services with more services for their clients, with no increase in their funding. The measures of this public benefit can be valuated and validated by third-party audit. Investors make these investments principally for a monetary return that is a portion of the value of the social impact.

The key to public gain, in Social Impact Financing, is private success in finding and employing social innovations that enable agencies and their staff to generate substantial, measurable, valuable and valid social returns. Because return on investment is a function of the social returns that constitute public gain, investors will ensure that public gains tests are applied throughout the investment process. Applied to increasing care productivity, standard business measures of productivity provide reliable measures of business benefit and can be applied to publicly-funded professional services. Based on the use of staff time, increases in productivity can be reliably valuated by comparison with baseline costs. Productivity measures and the value of the services that productivity increases generate provide a reliable foundation for validating the value of public gain by audit. The measures that will attract investors are the same measures that will assure government of the value of public gain.

Tax Incentive

The risks of developing and deploying productivity changes are familiar in the private sector. Turning private experience to public ends requires a public incentive that government can control through what will be years of investment and change. While Social Impact Financing can be administered directly by government, it can also be administered indirectly, as a tax incentive, at lower cost. Having auditors report private investments and social returns in public savings works well within the annual tax cycle. Annual claims for tax credits provide oversight of investment costs and social returns at the same time, and this level of transparency facilitates government control of the critical ratio in these investments of public to investor returns. Tax incentives bring government participation after the fact of both the investments and the savings, minimizing public risk in seeking and achieving public savings.

Growing Public Savings

Social Impact Financing provides an incentive for private investment to generate public savings in publicly-funded healthcare and social services. As the private sector embraces care productivity innovations, private investments will grow substantially. By the nature of this financing model, the value of public return on, for example, $500 million in private investment can be expected to grow, in lock step, to $2.5 billion in savings, in the form of more services for clients with existing public funding. The incentive to private investors, of a portion of the value of proven public gain, ensures continuing investment, not only in the deployment of proven social innovations, but in the search for new ones. Social Impact Financing commercializes public return on private investment, putting private capital to work for public gain. The economic benefit of public savings, with the social benefit of more and better healthcare and social services for Canadians, represent a sound political investment.